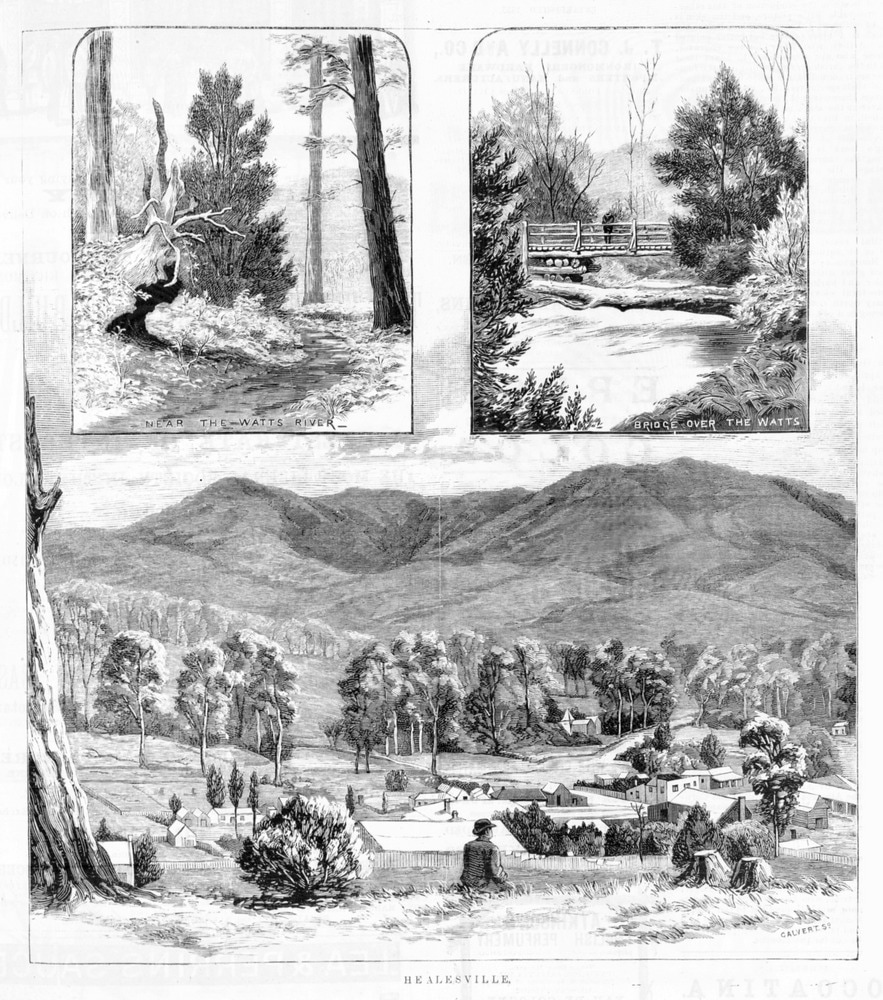

A visit to the Falls of the Watts

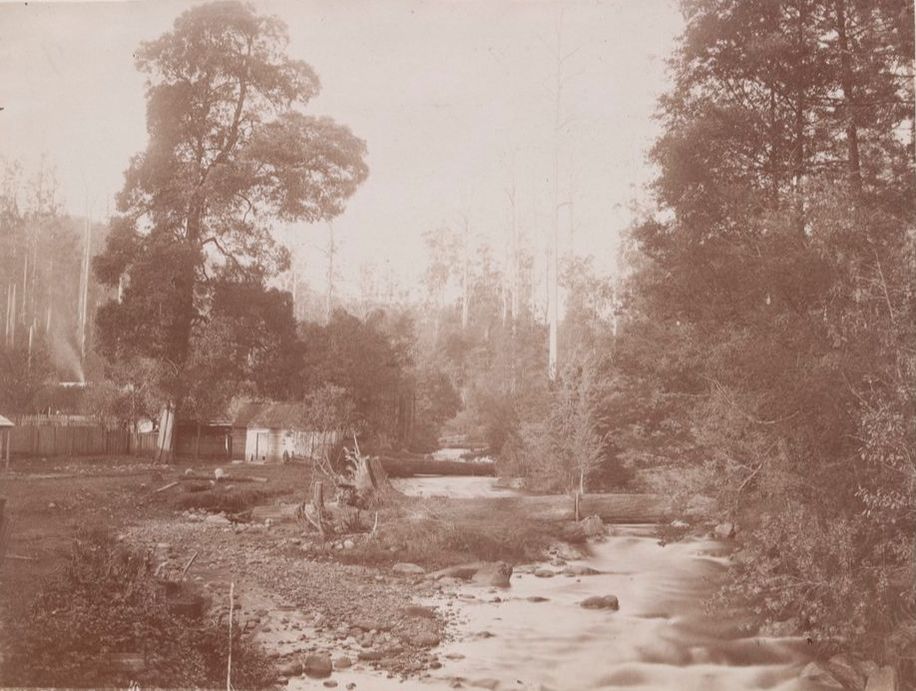

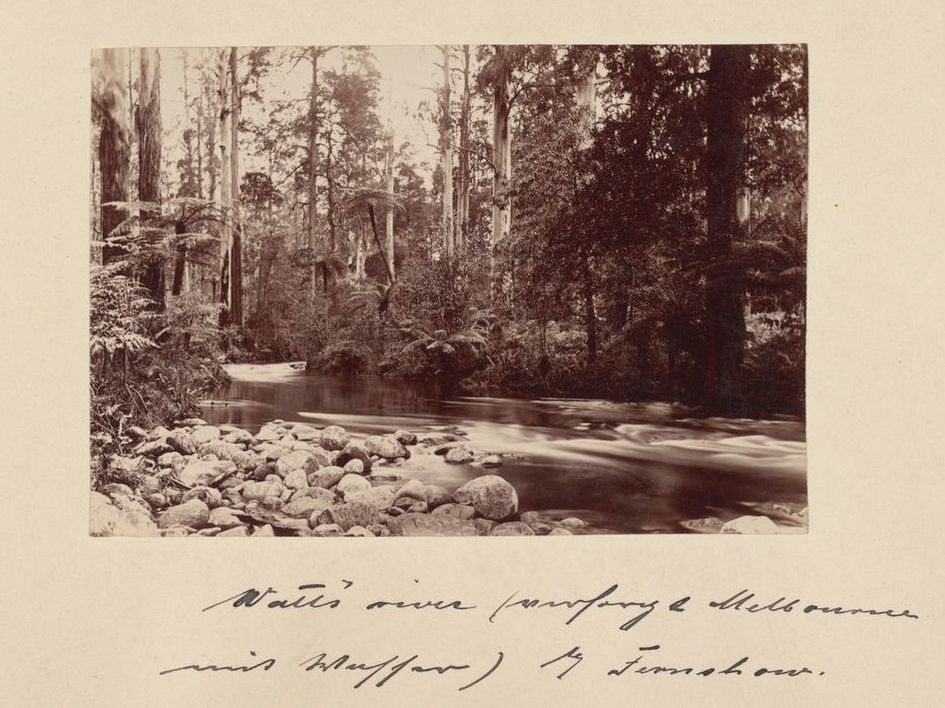

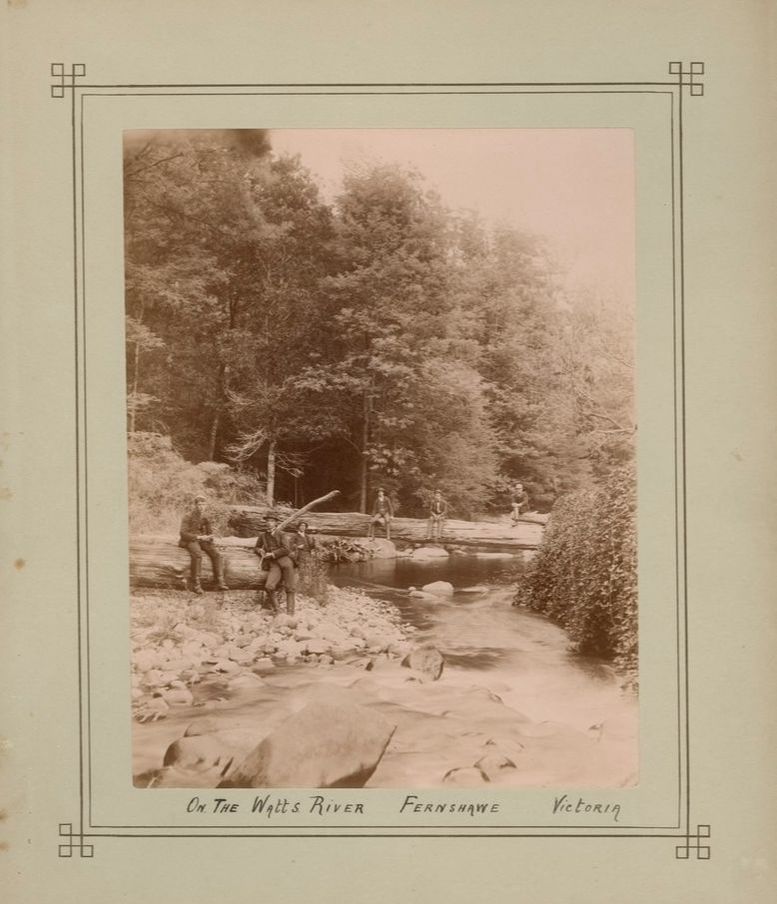

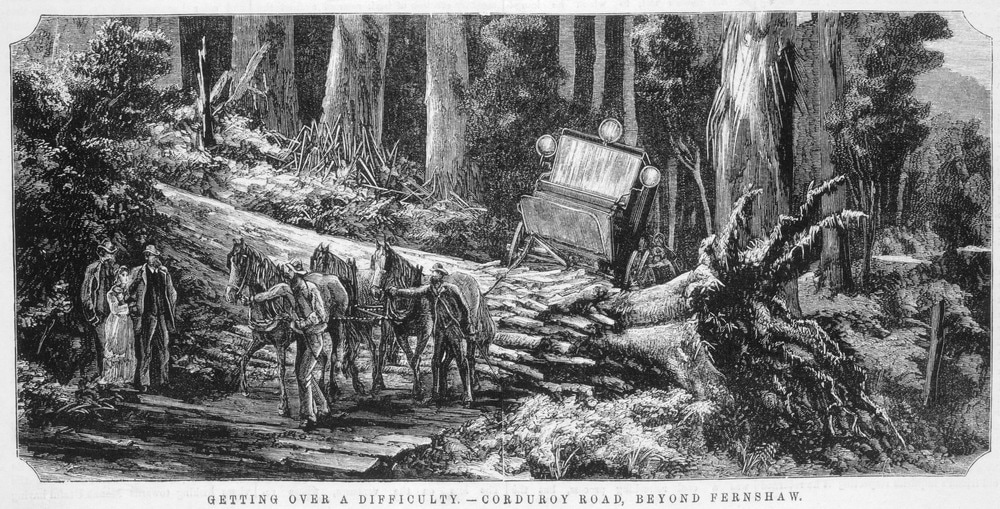

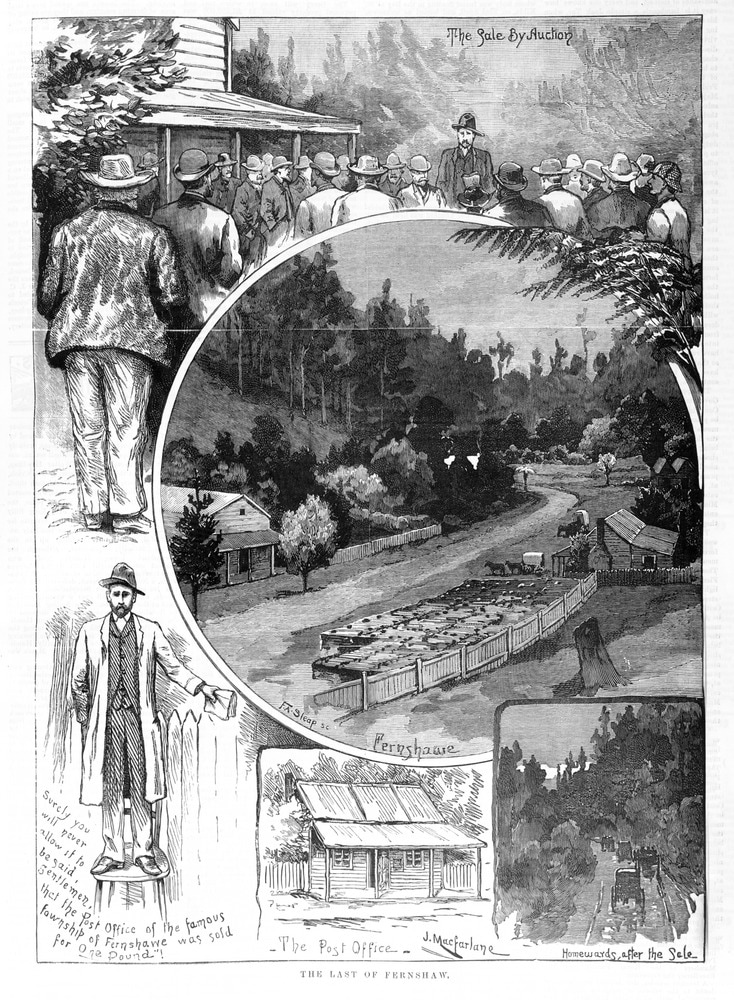

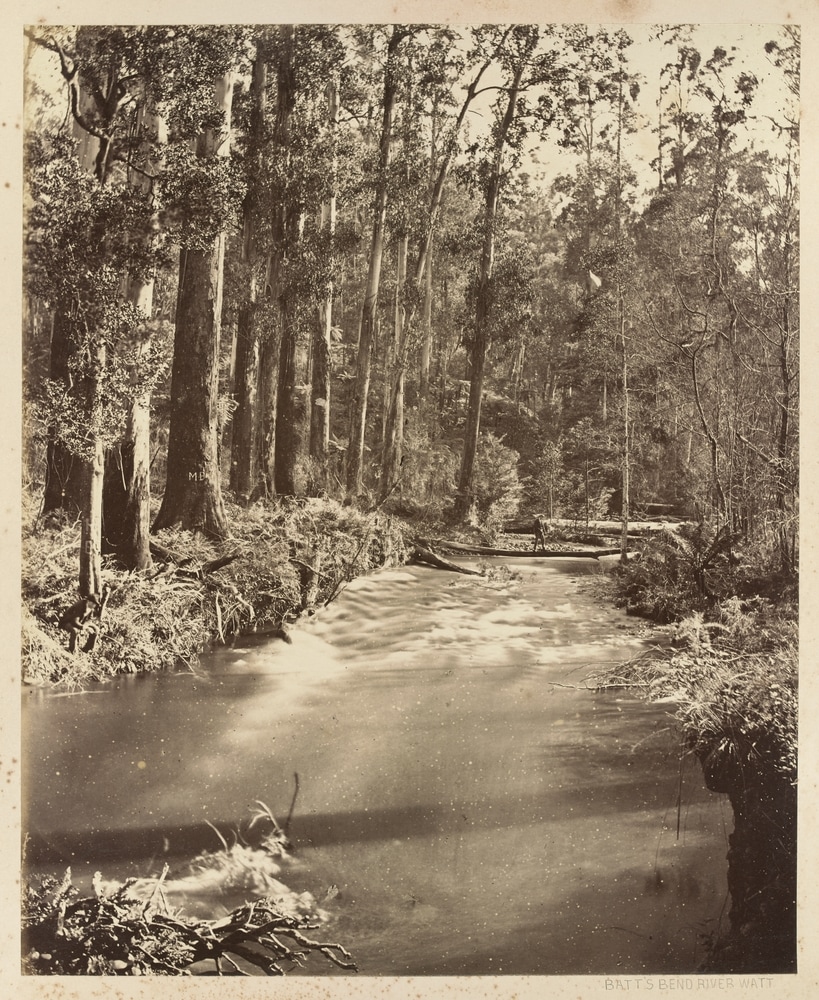

Dwellers on the banks of the Yarra, watching through the driest summer its ceaseless flow and witnessing its devastating floods, few of of us ask ourselves what its upper waters are like, and fewer visit them. And until the want if a direct road to Woods Point goldfield caused the opening up of various tracks, all of which touches at some point or other some of the affluents of the Yarra, such a visit would have been nearly impossible. Now, however, as digger and carrier have lead the way, the tourist may follow. The Watts, one of the principal affluents of the Yarra, a visit to the falls of which I am about to describe, is crossed by the present coach road from Melbourne to Woods Point before entering Healesville and again on entering Fernshaw. At the former place it is a dark and silent stream flowing with a strong current between steep banks, at the latter it is a torrent of clear cold water rushing over pebbles and boulders with a roar that can be heard a quarter of a mile off. Travellers along the Woods Point road, whether bound on business or pleasure, generally cross the Watts at Fernshaw, ascend the Black Spur and so see and hear it no more. The old pack track used to follow the course of the river for about four miles above Fernshaw and then turn off. Above that point the Watts has rarely been visited by white men, and as I have been informed in Fernshaw, not more than half a dozen white men, before the party of which I was one, have ever seen the falls.

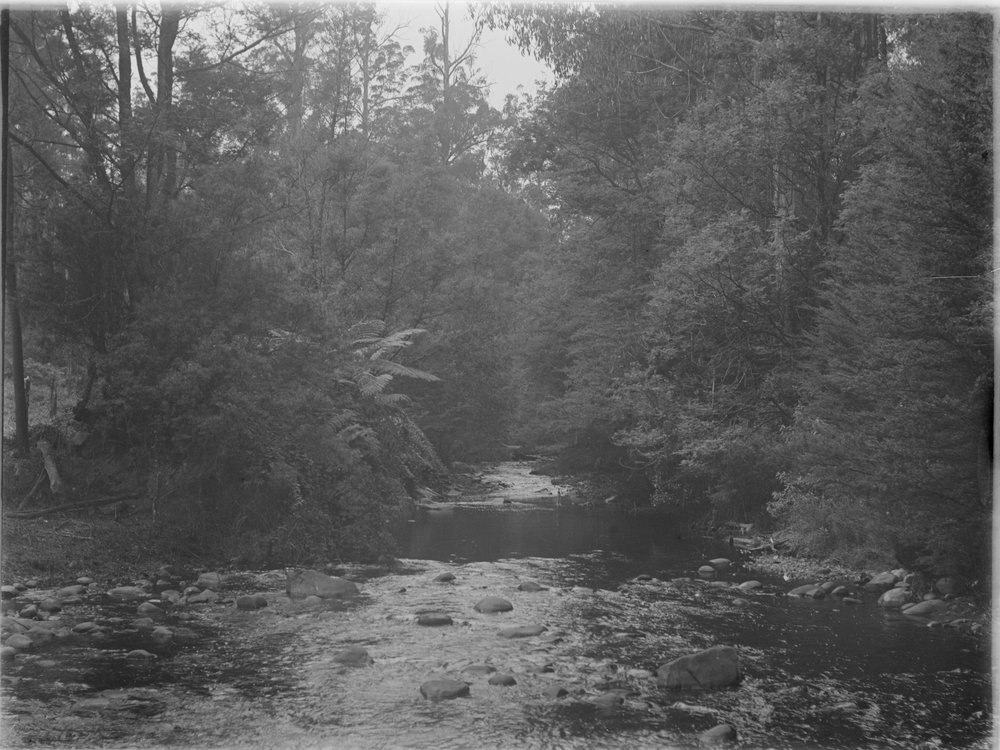

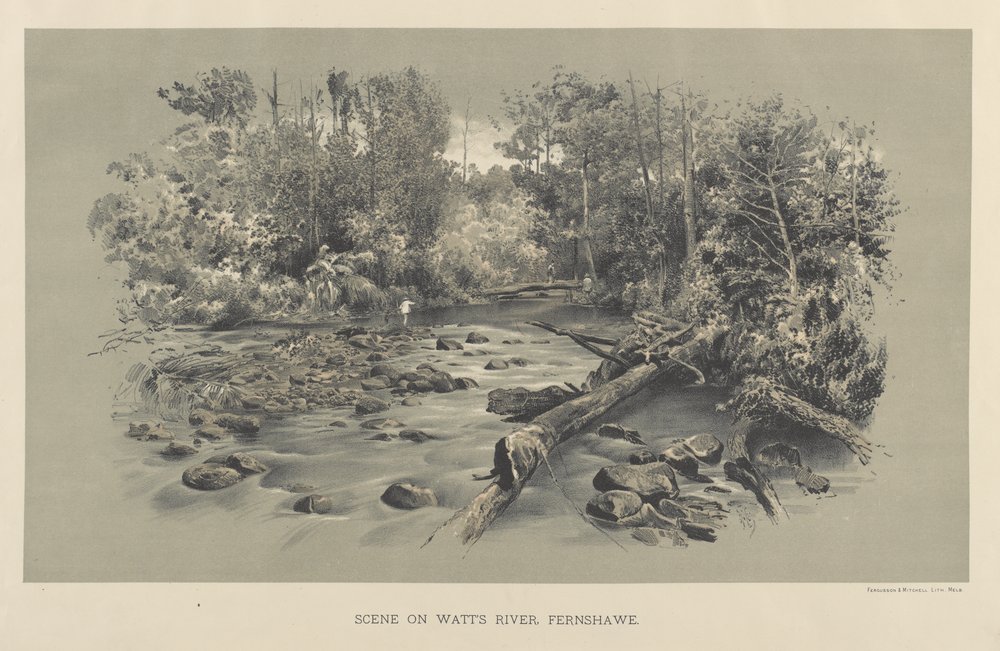

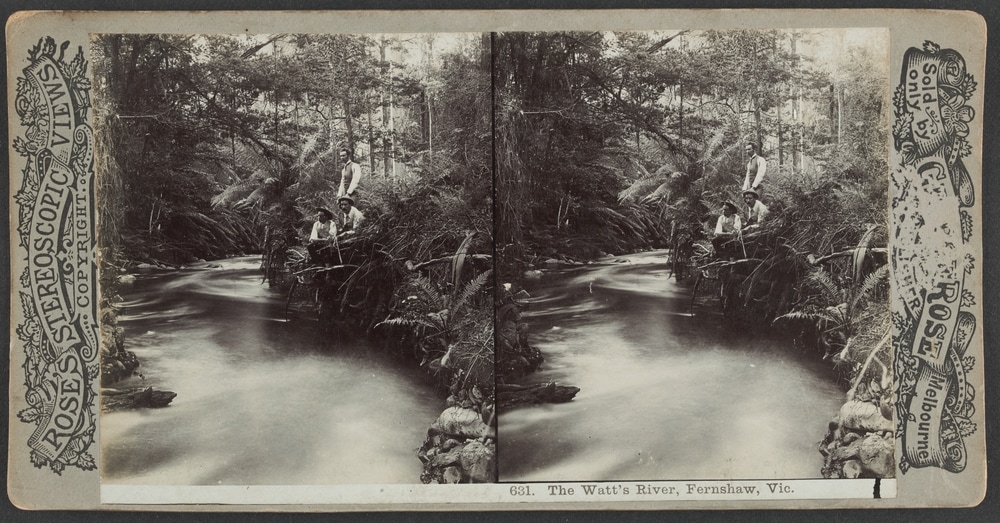

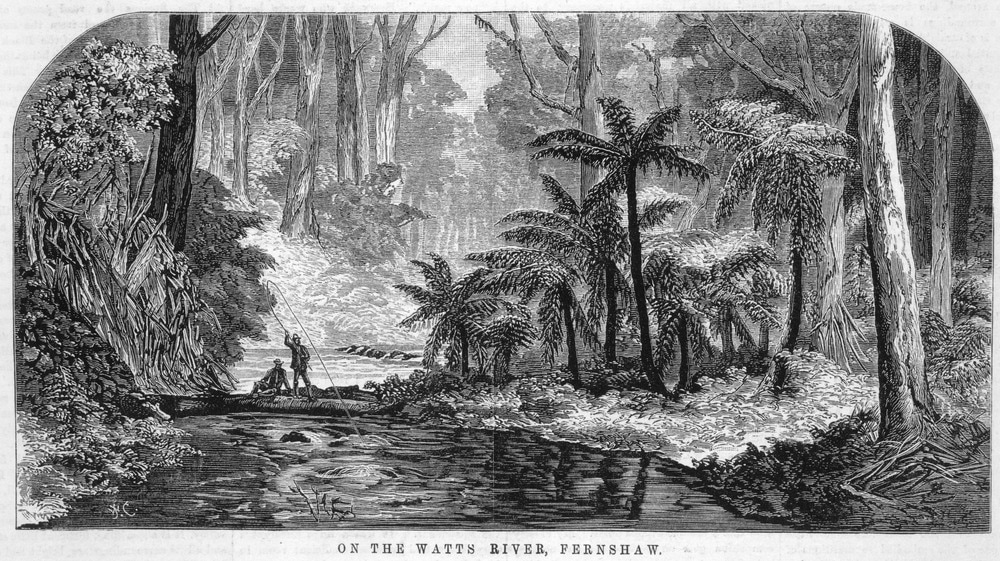

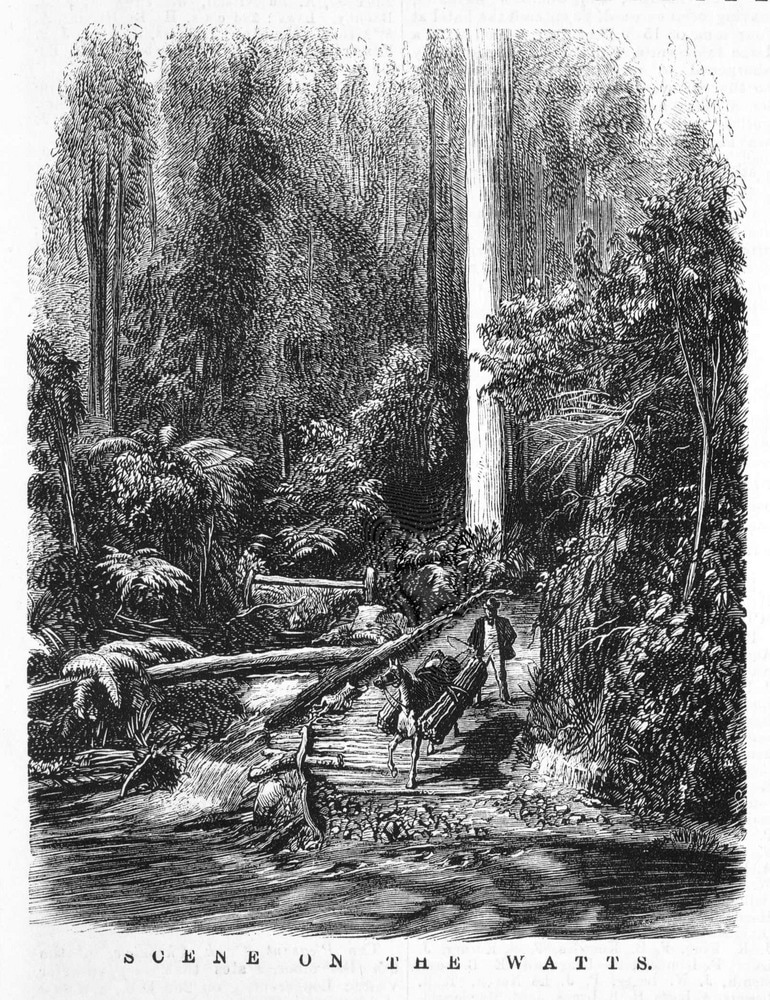

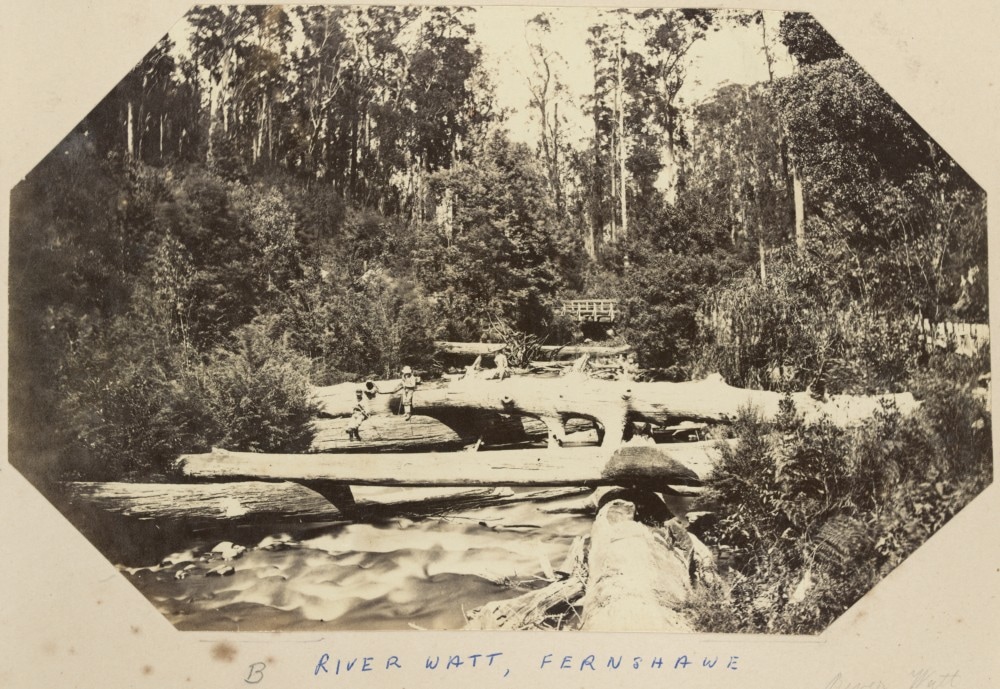

Fernshaw is a small township situated on a little piece of flat ground, not unlike the bottom of a punch bowl, surrounded by the Dividing Range and its spurs. The Watts, on approaching Fernshaw, flows in a generally westerly course between the Dividing Range on the north and Mount Juliet on the south, and the falls are some distance above Fernshaw. We started from Jefferson's Watts River bridge Inn, where we had been staying since the previous day, having been delayed by the rain, at about four in the afternoon. We each carried a swag, consisting of blankets and provisions, and we were furnished with directions from Mr Jefferson, who is one of the few persons who have visited the falls. For about two miles from Fernshaw there is a drat track which crosses a creek, a tributary of the Watts, and then runs between the river and the creek. So far our course was easy; but at that point the dray track re-crosses the creek and leaves the river, and was of no further use to us. The old pack track, indeed, had followed the river in the direction we were going for two miles further, but having been long abandoned it was completely grown over that no sign remained to show that it had ever existed, and the first step off the track took us into a jungle of fern an wire grass above our heads and concealing from our view a network of fallen logs. Perhaps some of your readers may not know what wire grass is. As its name implies, in form and strength it is like wire but it is also sharper than a file; moreover while unlike a creeper, it is stiff enough to grow to a considerable height without external support, its stems become matted together with one another, and also with anything else they may come across, but it is too pliant to cut with a tomahawk. Walking through this jungle was impossible - one had to roll as best as one could on to the top of the grass, and gradually kneed it down till it became firm enough to stand on and take a fresh roll forward. We began to fear that if all the way to the falls was like this we should never get there; but after about 50 yards we got into clearer country. We seemed to be travelling on a flat tongue of land between the river and the creek the track had crossed, keeping as much as possible under the fern trees, where we found the ground clearest; still every two or three steps we had to scramble over a log or a mass of fallen broughs, or force our way through a net of wire grass. Our principle guide was to keep within the sound of the roar of the river. We were going to pass the night in a deserted hut, which stood on what had been the pack track, and had been used some purpose in connection with that track. Since the track had been abandoned, the hut had been abandoned also. It is commonly known in Fernshaw as "the frame". It was necessary to find this hut to pass the night in, as, though we had our swags with us, outside it we could not expect to find sufficient clear ground to lie down on. At last towards evening, we caught sight of the frame. It was buried all round up to the eaves in wire grass, and in some places the wire grass was over the roof- it had grown all over into the chimney - it had found its way through the shingles and was hanging down to the ground; tall ferns were growing up from the earthen floor and trying to find daylight through the roof. The hut had two holes for doors and two for windows, but all except one door were stopped up by the grass. We set about at once, cleared away the vegetation from the inside of the hut and of the chimney, got water and firewood, cut fern for a bed, and generally made ourselves comfortable for the night. Our supper was soon disposed of and we were snoozing with our feet to the fire, and the roar of the Watts for our lullaby. We did not continue our journey next morning till a little before 8, allowing that time for the dew to get off the grass, which, where the grass is over one's head is a consideration; when; having left our swags in the frame, after noting its situation and blazing trees so that we might find it again, we proceeded as before until the tongue of land we had been following was terminated abruptly by a steep hill. Soon we found ourselves on a slope struggling forward over fallen logs and wire grass. We determined to descend to the bed of the river, and in doing so found a creek joined the river just above the hill we had climbed, and that for our timely descent we should have been following this up instead of the river which thenceforward we generally kept in sight. From this point up, the hills generally sloped steeply, and more steeply to the river, which ran with a current of ever increasing rapidity as we neared the bottom of the fall. All the rocks of which the riverbed was composed were ever covered by the water were warn smoother than glass. These out of reach were covered with moss and fern. Our way was continually obstructed by the trunks and branches of large trees which had fallen from the hillside overhanging the river and lay with their broken heads in the water, and their roots high up the slope. Perhaps the principal part of the labour of ascending the valley of the Watts consists in having increasingly to get over these fallen logs. The broughs of some of them lately fallen were still covered with withered leaves. The trunks of others remained quite sound, while the inside had rotted away, and in crossing we had to take care lest one dropping through a hole in the shell should slide down the slippery shoot into the water. The slopes, except where the rock was, were covered with soft mould, the products of rotting leaves. The native myrtle with its thick dark glistening leaves, lined the river. Fern trees and sassafras trees covered the slopes. Rope like creepers hung from the broughs of the myrtle whose strangely gnarled and twisted trunks were covered with moss and fern. Every now and then a clear stream would come trickling or leaping, as the case might be, down the mountain side to join the river. Then one would see a long steep gully of fern trees stretching far up till it was lost to sight. One of these streams in particular that I recollect came into the river in a series of little waterfalls, making one of the prettiest objects I have seen. There is a dim twilight in the valley; even at midday one can occasionally catch sight of a hill top covered with trees glistening like silver in the sunlight, but on the river's brink there is a perpetual shade. No sound is heard but the cry of the lyre-bird and the roar of the water. So we proceeded up the valley, which grew darker and deeper and steeper, while the river ran with an ever increasing current, occasionally forming a deep black pool, and occasionally a short cataract, till suddenly the hills closed in on both sides, and we were at the foot of the cataract. Henceforward we had to leave the river bed, for the torrent washed the foot of the slopes on each side, which now became steep that one could barely stand on them, in fact but for the fern trees and sassafras trees, this would be impossible; so often clambering on our hands an knees we went on up the slope. The roar of the water had become so loud we could hardly hear one another speak. For a long way up the valley, distinct from the sound of the broken water at our feet, we had heard a deep, intermittent thump; this we took for the sound of the distant fall, and from its deep tone, and from our hearing it above the roar of the water at our feet, we judged that it must be the sound of a very high cascade which we accordingly expected to come upon shortly; and we heard it now louder, now fainter, now louder again, we seemed to be following will-o-the-wisp. As we entered the gorge I have just mentioned this sound was louder than ever, and we thought we should soon be coming to the cascade. We expected at every turn to see it, but after toiling for two hours up the side of the gorge which was like a huge crack in the mountain no clear fall of great height was to be seen, while the sound grew fainter and fainter, but only a long cataract. The top of this we tried to reach but had to abandon the attempt otherwise we should have time to return to the frame before dark. On our return, we ascertained what the noise was which had deceived us. Near the foot of the cataract, which can hardly be less than 500 ft. from top to bottom, the water runs with a prodigious velocity. Whenever it comes on a large boulder, an immense jet of water instead of clinging to the boulder shoots forward from the top of it, and strikes the rocks some way in front; it is then stopped for a moment by its own recoil, and then shoots forward again, thus producing the thump, thump which seemed to shake the ground, and which we mistook for the sound of a distant fall. The Falls of the Watts, as far as we saw them, did not present any clear perpendicular descent of more than 15 or 20 feet, certainly none equal to the first fall of the Steavenson above Marysville. The cataract, however, is very high - higher a good deal, I should think, than the entire cataract at Marysville. The rainbow tints, also which, the sunlight gave to the falls at Marysville were wanting, but the deep shadow of the mountains and trees gives a wierdness and gloom to the scene that is, perhaps a compensation. Moreover, not withstanding the great length of the cataract of the Watts on account of the windings of the gorge, and the thickness of the vegetation, one can for the most part only see it in little bits: the best views one could get would be in this wiser down below one, through a break in the trees, one would see the water a foaming cataract. It would then be hidden; a little further down it would be seen again smooth and transparent, sliding down a slope of rock with lightening speed till it was again hidden. Still lower one would see it disappearing over a ledge. Again the broughs would intervene, and again lower and yet lower it would gleam through the trees, till it was finally lost. At our highest point we were standing on a steep slope of slippery mould covered with sassafras and fern trees. High above our heads on the opposite slope we could see tall timber glistening in the sunlight, but we seemed to be little nearer to the opposite slope we could see timber glistening in the sunlight but we seemed to be little nearer than we were half an hour before, so we returned and were not sorry, just as darkness was closing in, to reach the frame having been walking and clambering for 12 hours. Good bushmen at any rate if they were acquainted with the gullies of the Great Dividing Range, would no doubt have been able to get over the ground quicker than we did. If it had only been by knowing how to avoid the worst patches of wire grass, and the steeper parts of the valley and if there were sufficient number of visitors to the falls of the Watts to make it worth anyone's while to lay himself out to act as a guide, the difficulties of the way might be much lessened, and in addition, some point of view would probably be discovered from which a large portion of the long cataract could be seen at once. But until, what is very improbable. a track is cut, the cataract of the Watts will long thunder in its solitude seldom heard, and more seldom seen. The valley of the Watts has one advantage over the fern-tree gullies of the Dandenongs which when I first saw them remind me of Shelley's lines

"The path

by cedar pine and yew

and each dark one that ever grew

Is curtained out from heaven and wild blue:

more to come

RSS Feed

RSS Feed