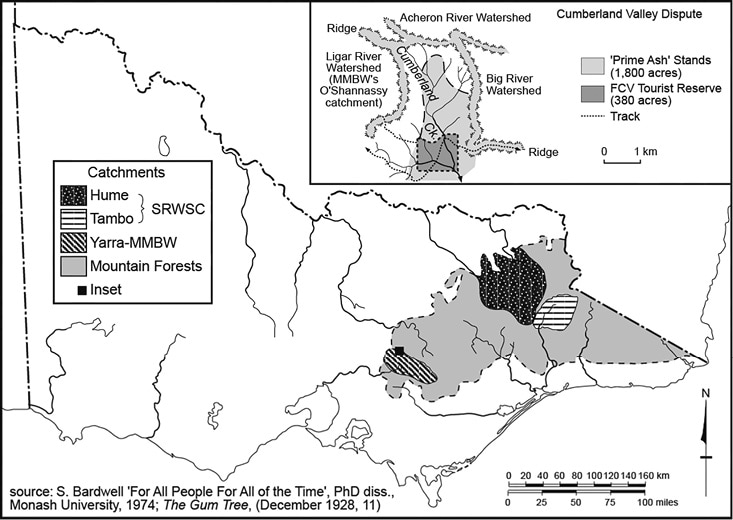

The magnificent stands of Mountain Ash at the head of the Cumberland Valley near Marysville had already gained an international reputation as the tallest grove of hardwoods in the world and a pristine beauty spot. But in silvicultural terms, according to the FCV, the trees were fast approaching their optimum commercial age and would soon ‘go to waste’ if allowed to become ‘senescent’. The implicit notion that forests needed human intervention lest they decay or ‘rot’ aligned with modern forestry economics versions of opportunity cost and declining marginal returns. The idea of decay had also been regularly used by earlier Lands and Agriculture ministers to justify forest clearance and even by some of the leaders of the AFL keen on maximising forest utilisation. It was already a source of division among ‘conservationists’ and ‘preservationists’. The Forests Minister’s insistence that ‘scientific forestry’ would ensure that no damage was done to the beauty spot and that it was the Cumberland Falls not the trees that attracted tourists merely inflamed the situation. The agitation was initiated by a well-crafted press campaign by the Marysville Tourist Board that was soon taken up by the Melbourne newspapers, and was immediately supported not only by the FNCV but also by the AFL and ANA. Intervention by the influential Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA) led by eminent conservationist Charles Barrett soon followed, and a series of well-attended public meetings and deputations were held over the next few years. Prominent individuals such as painter Arthur Streeton noted the ‘endless beauty of the green and living forest’ and pleaded ‘on behalf of all Australian artists’ against the ‘proposed vandalism’. Forests Minister H. F. Richardson made minor extensions to the planned reserve, and promised a square mile reservation as a Soldiers’ Memorial in 1929. The concessions could not placate the agitators, especially those in the FNCV and the TCPA who, unsuccessfully, called for the area to be declared a National Park.

The dispute dragged on for more than 20 years; the successive Forests ministers never lost sight of the opportunities for large royalties from the logging, and always resisted attempts at permanent reservation by Order in Council, which would make forest reserves safe from ministerial whim. Strong protests were again made in 1929 by 16 major and numerous minor organisations. Mounting demands from neighbouring Warburton sawmillers to access the nearby forests added to the difficulties. The resurgence of gold-mining during the Great Depression saw the Cumberland groves threatened by water diversions from the Cumberland Creek for mining purposes and this set off a new round of agitation in 1934. The following year Barrett’s TCPA vigorously renewed its campaign to establish the area as a National Park but little was achieved despite the FCV Chairman’s insistence that the area would be preserved for all time. A few months later, agitation for logging was renewed by the Hardwood Millers’ Association and listened to sympathetically by the new Minister of Forests. The AFL renewed its campaign in 1935, as part of its broader push to preserve the watershed forests. The campaigns continued over the next four years and the area, by then claimed to be Victoria’s most popular tourist spot, only narrowly escaped destruction by the catastrophic Black Friday bushfires in January 1939. The Cumberland Valley forest was temporarily reprieved by timber supply from the enormous fire-killed timber salvage operations elsewhere that ensued through the war years. Nevertheless, parliament again entertained plans to log the area in 1948 to relieve the timber shortages during the postwar housing boom. Unfortunately, most of the remaining ‘big trees’ were destroyed by storms over the next 30 years.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed