Warburton bike tracks. What a great idea. They will go right past the Yarra Ranges Bush Camp5/26/2018 In an Alpine Garden

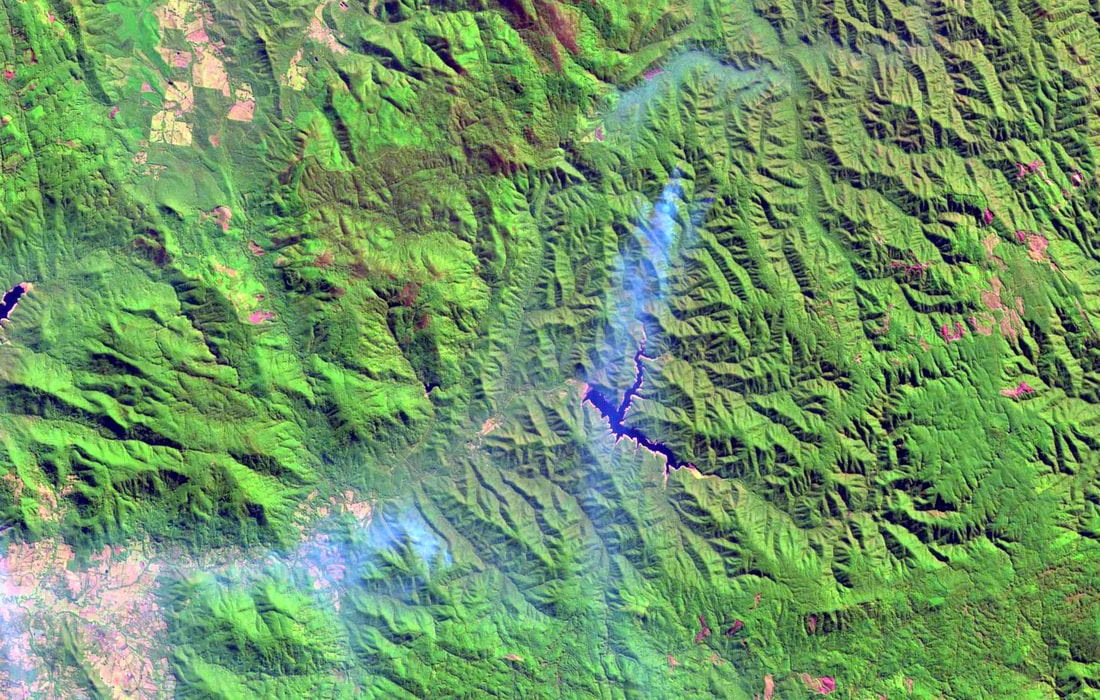

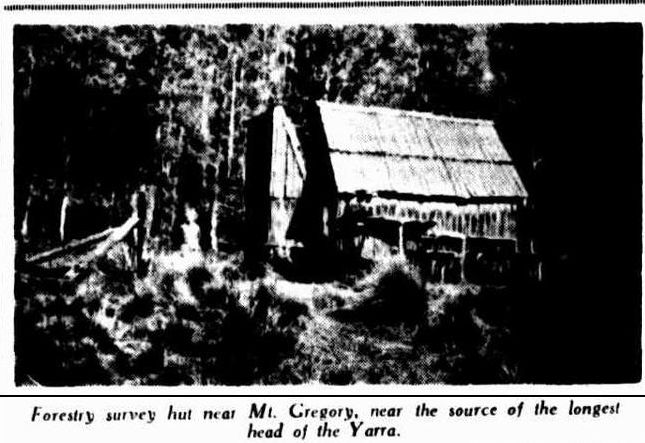

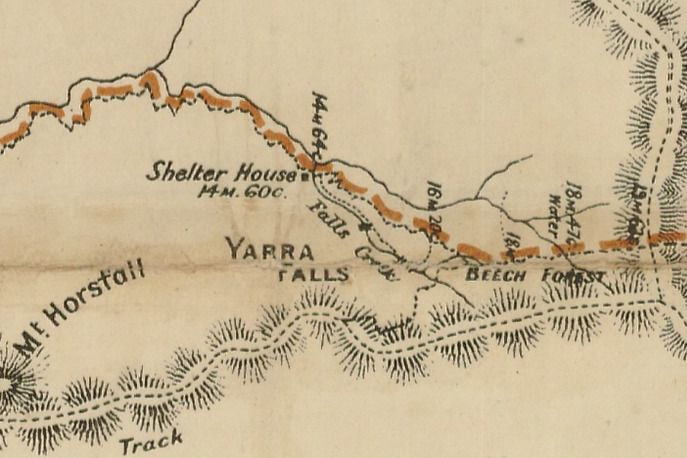

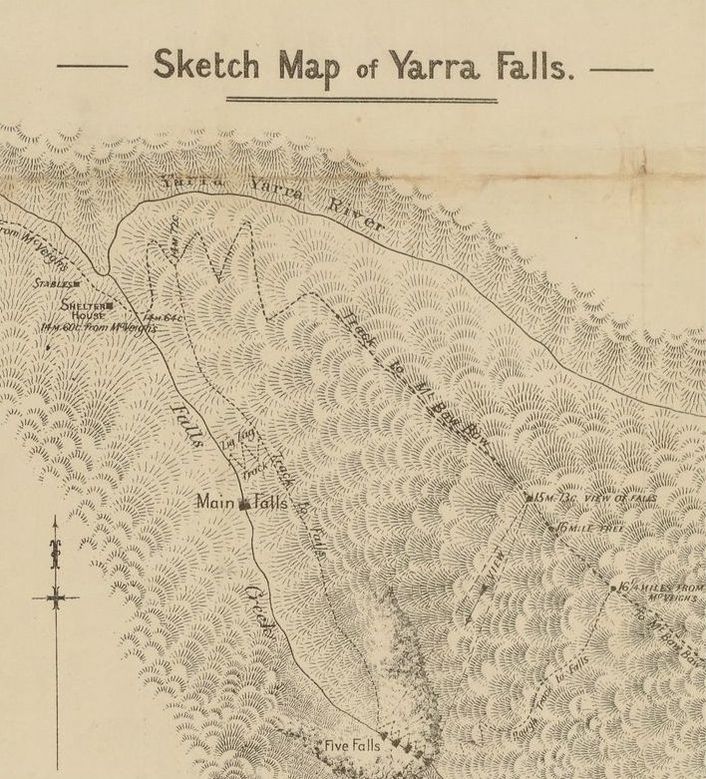

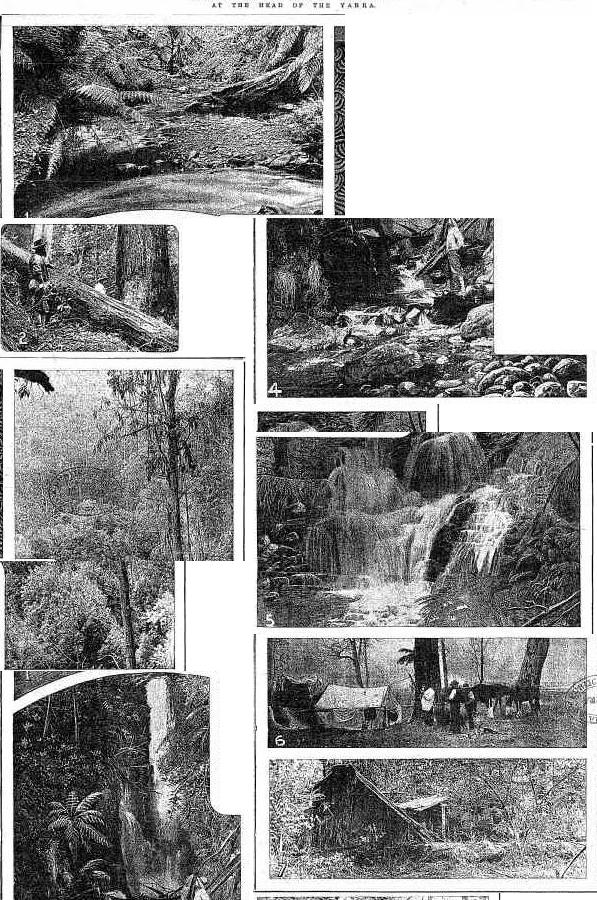

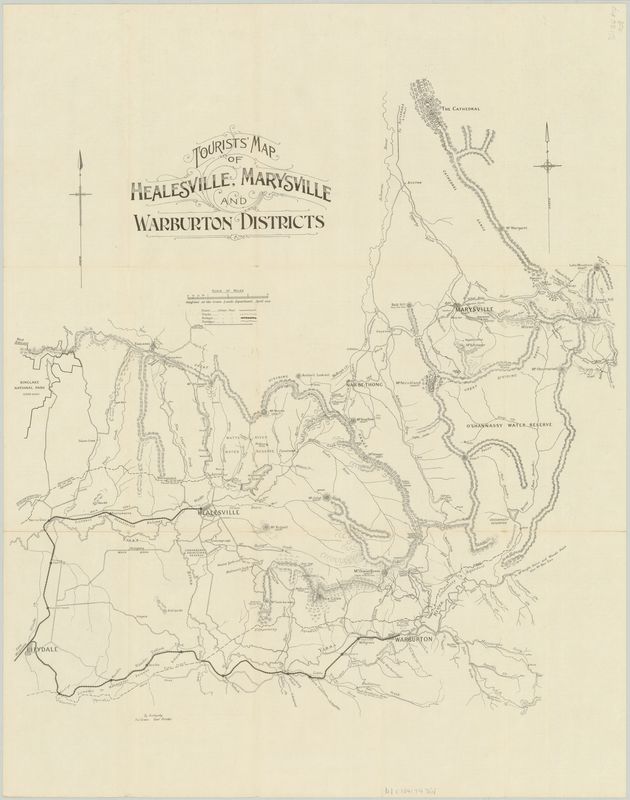

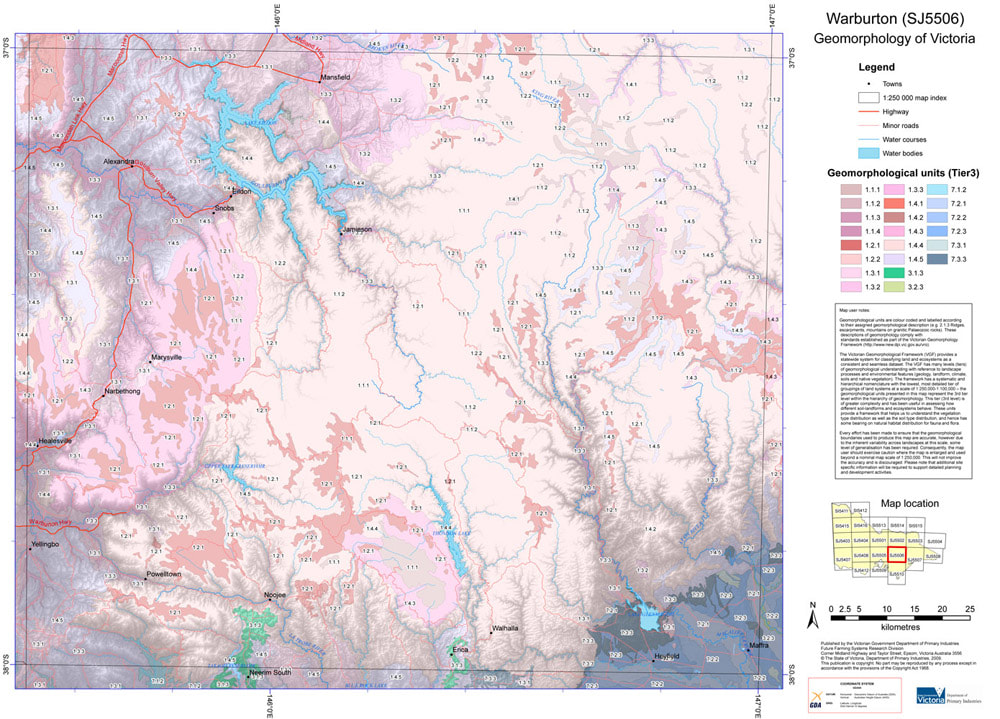

By W. H. Nicholls Mount Erica and its surroundings on the Baw Baw mountains in N. E. Victoria between the months of December and February ( the spring of Alpine regions ) is gay with wildflowers. A visit at this period would prove to flower-lovers that for variety and wealth of floral beauty, our flower gardens hold their own with gardens of any other country. Mount Erica ( 5,000 ft. ) is on the eastern extremity of the Baw Baw Mountains, and is accessible from Walhalla, the famous mining township ( which is distant about 14 miles ) or from any of the log sidings and stations en route from Moe - preferably Thomson or Erica. The most popular route, but the longest, is via Warburton and McVeigh's. I prefer the direct, via Thomson route, the stiff uphill climb of Mount Erica notwithstanding. It is one or 1 1/2 days journey, according to the circumstances of travel. By way of McVeigh's the journey takes three to four days, over not easy miles, but the scenery is superb. On Falls Creek, 15 miles from McVeigh's many of the tree ferns have fronds measuring 15 ft. long and 3 ft. wide. The last and most enjoyable expoerience of a party of which I was a member was of a camp of five days on Talbot Peak, Mount Erica. The peak is really a spur of Erica and at the head of Talbot Creek. Both were named in honour of Sir Reginald Talbot when he was Governor, at the inauguration of the "through" track in 1907. We spent our time exploring the large morasses and many valleys hereabouts. We went over Mount St. Phillack ( 5,140 ft. ) to beyond Mount Whiteaw ( 4,875 ft. ), a distance of approximately 10 miles. Mount St. Phillack is the greatest elevation on the plateau. We found botanic life at its best, and many splendid sights in the region will often be recalled with satisfaction. At the foot of Mount Whitelaw, and on the creek which bears its name, we found the Alpine heath ( Richea Gunni ) in full glory. The beautiful spike of creamy pearl like flowers, combined with the palm like leaves, the light-brown protective shields of the buds, and the red stem form a picture of unusual beauty. On the summit of Mount St. Phillack and in many favourable places towards Mount Erica, fine species of orchidaceous plants were seen in great profusion. The most numerous was the green bird orchid ( chiloglottis Muelleri ). The flowers are not of a brilliant colouration- just a modest but pleasing shade of green, with some purplish markings. This was named after Baron Sir Ferdinand von Mueller, probably the first man to "botanise" in these wilds. Two other kinds, conspicuous by their numbers, are popularly known as leek-leaf orchids ( Prasophyllums suttoni and Taggelianum ). They receive their respective names from their finders, two Melbourne naturalists. Both have delightful perfume, and they are restricted to these regions. Their numerous flowers are somewhat indefinitely coloured and are arranged upside down on the stem. The mountain greenhood ( Pterostylis alpina ) is another interesting orchid of these highlands. The hood-like flowers are neatly fashioned, and very softly coloured in shades of green and white; herein lies their strange charm. At the head of the Yarra River, and also at the Thomson River bridge, close by the home of our glorious lyrebird ), we found many colonies of the plants. Their setting under the fairy-like beeches among the luxuriant ferns seemed to suit them to perfection. The most beautiful orchid - and the most conspicuous, by reason of their bright colourisation - is veigned sun orchid ( Thelymita venosa ). On sunny days the margins of the morasses are gay with myriads of the dainty flowers. Most of our sun orchids have blue flowers; but this species, unique as it it is, has in addition, rich purplish-blue veinings on the flower segments, and inside the flower is a pretty column with golden-hued crests. It is exceptionally plentiful all round Mount Erica. The golden Senorious, with their marguerite-like flowers, make the way very pleasant for the travellers from a point just after leaving McVeigh's to just before reaching Mount Whitelaw. Three kinds grow in abundance in the comparatively open spaces, under the beeches and the eucalypts. They seem able to hold their own, even with the tenacious bracken fern. Other mountain plants occurring here include the Alpine mint bush ( Prostranthea cuneata ). January is the best month for its flowers. We have seen dozens of this attractive shrub, many 5 ft. high; a wonderful wealth of bloom. The individual trumpet shaded flowers are heliotrope, with purple spots inside the throat. The foliage has a strong pungent odour. The are many other kinds of flowering shrubs in these wild gardens round Mount Erica, all beautiful and some very rare. Not one of them has found its way to our home garden - as yet ! We have nothing as splendid among everlasting flowers as the unique scented rosemary everlasting ( Helichrysum rosmarinifolium ). The flowers are born in myriads, and at the height of its season the bushes are like masses of snow. The snow daisy bush ( Oleria Lyraba ) is also excepyionally abundant everywhere, on the slopes of Mount Erica and the adjacent hills. It resembles the Easter daisy in cultivation, but this mountain plant has far more blossums to its branches. The houry daisy bush ( Olearia Frostii ) has to be the largest blossoms of all the daisy bushes of our mountains. The flowers are white, and the plant having been named after a Mr. Frost the foliage properly has a frosty appearance. It is numerous on Mount Erica, and also on Mount St. Philack. Many of the bushes were much admired for their unbroken florescence. Two of the choicest flowers round the Morasses on Talbot Peak and near Mount Whitelaw are the Baw Baw berry ( Wittsteinia vacciniacea ) and the Alpine heath ( Epacris Bawbawensis ). Both are true heaths, and have cream and white bell shaped flowers respectively. The fruits of the Baw Baw berry are edible. The flowers of the Alpine heath are borne in large clusters at the terminals of the branches. Both of these heaths favour the damp situations under the twisted white-flowing snow gums. Growing among the daisies and heaths are trigger plants ( Stylidium graminifolium ) with rich magenta flowers. On the low lands they are always small, and the flowers pale-coloured; but at this altitude the plants are of a robust habit. Each individual flower has a sensitive trigger-like arrangement for the fertilisation of the flower, hence the name. Another daisy to be found here is the silver daisy. The plants are literally in tens of thousands round the morasses and lining the margins of the creeks. They have flowers very like the shasta daisy, but this mountain daisy has rich purple markings on the reverse side at the white petals. Botanically it is known as Celmisa longifola. Among the many smaller plants hereabouts ( and there is a multitude of species ) we must not forget the violets ( Viola hederacea ). Wherever we tread the carpets is of violets. The flowers are often large 3/4 in. in diameter, and the stems long. Most of them are heliotrope, with richer markings. Around the convenient hut on Talbot Peak the eye alights on them in myriads. They seem to be assembling for invasion of the rich lands below. THE CONTRIBUTOR. AN EXCURSION TO THE UPPER YARRA FALLS. By G. No. II. We struck camp next morning at half-past nine. Just after starting we noticed a tree marked W. From this we understood that we had been encamped on the two mile water. This made our march of the previous day a little over 8 miIes, The height of our camp measured by the barometer was 1700 feet above McMahon's, We proceeded along the south watershed of the Yarra in a general easterly direction. The prevailing charactor of the country was the same as on the evening before, The track was often perceptible as a sort of avenue through the scrub, though in the clearest places knee deep in ferns and wire grass and obstructed by logs. We passed through several saddles separated by small sills, At about twelve o'clock we could see a great spur coming in to join the ridge we were following from the north - that is on our left, This could be nothing else than the right watershed of Alderman's Creek. We were, therefore, making good progress, and might hope to reach the Yarra that night. So we went on for another half hour, when our horse, in getting over a log, slipped and fell; he could not rise again with the pack and we had to unload him, but he was none the worse. As we began to ascend the hill we found the sides and top of it covered with huge logs hundreds of foot long, as if it had been cleared by a survey party, The interstices between them were filled with tall bracken and scrub with white flowers, and the track seemed altogether ob literated. We made our way very slowly round and over the logs, and presently the horse got another fall, and we had to unload and reload again, There was a good look out from many places down the valley of Alderman's Creek and of the ranges across the Yarra, We found the top of this mountain was 1200 feet above our camp of the previous night, or about 4000 feet above the sea level. It is unnamed on the maps. We christened it Mount Horsefall. The fallen logs gave it a pre vailing white appearance, but it contrasted with the pale green which had hitherto characterised the crest of the range. At about four o'clock we began to descend a little, and get into a forest, in which the beech tree was the prevail ing timber, though largely mixed with tall gums and messmates. But little vegetation grows under a beech tree; what there was was the blue gum fern with the crimped frond I have noticed before. Moreover, the beeoh tree is seldom uprooted. It slowly decays as It stands and falls piecemeal, The ground in a beech forest is therefore encumbered by but little fallen timber. As soon as we got under the beech trees the track improved very much. They were mingled, however, with very tall messmates, from which large quantities of dry bark in strips 4 or 5 inches aoross and 30 or 40 feet long or more had fallen to the ground, and lay in large colis. These continually tangled our feet, and it was difficult to get free of them, One would continually find one was dragging a tail behind many feet long. On getting under the beech trees the prevailing tints again changed. The black earth was bare, and varied shades of brown or dark green met the eye In every direction. Towards the south and east the slope was so steep that we got a look out over Gippsland as far as the ranges in the neighborhood of Baw Baw. The earth seemed everywhere moist; in plaoes one could hear the water under one's feet. The traok oontinued slowly to descend, and our view became shut in on all sides. About s!x o'clook we found ourselves in a saddle. This we identified upon our tracing as about 6 miles from our camp of the night before And 4 milos from the Yarra. It seemed a likely place to find water. There were a few beech trees and messmates on the saddle, and a forest of white gums, tall, slender poles like the mast of a ship, 300 feet high at the least, with a tuft of foliage at the top. There was a fern tree gully coming up to the saddle on each side. The earth was black and moist, and for the most part bare. R. found a good stream of water a llttle way down on the south side of the saddle, so we determined to camp. We pitched the tent under two beech trees, whose thick foliage would protect us from any sticks that might be blown off from the gums, and made our bed of fronds cut from the ferns. When we got up the next morning a strong north wind was blowing, shaking the tall, white ferns like oorn stalks, bending them as if to break with a great roaring noise. We did not make a start until about half- past ten, when we at once began to ascend out of the saddle, and soon came out into the sunshine on to a hill covered with fallen timber and sword grass, and from which there was a good view of the opposite ranges. The logs had rotted and broken into fragments, and were therefore not the obstacle they had been on Mount Horsefall. After a little we again descended into a beech forest. Here the track was clearer than we had yet found it. It was obstructed by little else than small sticks. There was a little of the usual green fern, but except for that the ground wes clear of undelrgrowth on all sides. The dark foliage of the beech trees over head shut out the sky. In order to keep the track it was necessary to keep a sharp look out for blazes. After about a couple of miles gum trees again ap- , peared mixed with the beeoh trees, and we were again troubled by fallen tlmber. About the same time we found growing in the track tall solitary stalks of grass like oats which shot up with a stem as thick as one's finger, seven or eight feet high. Finding the horse would eat the two gathered bundles of it, as we went along. A little after twelve o'clock the horse got another fall getting over a log. We had to unload, and determined to have lunch, When we again made a start we found it had been raining heavily, and that the scrub was very wet. In a little while we got out of the beech forest, and began to ascend a hill covered with tall standing gums and thick bracken up to our shoulders. Through this we pushed our way, getting drenched through. When we gained the top of the hill we found our track ap peared to leave the rldge, and turn down the sideling to the north-east. After turnlng down on the sideling we were soon again in a beech forest, and out of the high wet braoken. In about half a mlle we came to tho creek, whloh was broad and shallow, scarcely covering the ground. It crossed the track from left to right- not from right to left, as marked in our tracing. The descent from the ridge to this creek was not more than 200 or 300 feet, and not at all steep, consldering it was on a sideling. We crossed the creek and ascended to tho ridge on the oppo- site side. Crossing it we descended on a slde- ling to the Yarra, which we at onoe passed over. It was a much smaller stream than that we have left at M'Mahon's, being about 30 feet wide and about up to our ankles, with, how- ever, a good current. The scene was a peculiar one. It was still raining hard. Heavy clouds rested on the tops of the beech trees from 50 to 70 feet above us, whlch lined the river banks and covered the slopes, and hung in festoons between them, but below it was clear. We had no tlme to stand and watch it, however, being wet through. We had to get to work and camp at once. In about twenty minutes we had a flre big enough to roast an ox. Having pitched our tent we looked about for something to make a bed of, and the best thing we could find was a heap of bark at the foot of a neighboring messmate. This we dragged in front of the fire and dried, after which we had our evening meal round the fire. We stood up round it for some tlme drying clothes, while the horse stood warming his nose on the opposite side of the fire. Finally we turned in. We were up at six the next morning. There was still a slight rain, We had breakfast, and at half-past eight we started in search of the falls. Our camp was shown by the barometer to be 2100 foot above M'Mahon's or only 500 feet lower than the top of Mount Horsefall. It was ; dlstant from Reefton by the road wa had come just 20 miles, or in a straight line about 15. Now, the Yarra did not change its level to any great extent between M'Mahon's and Reefton, or for some mlles above the latter place. The dlfference in elevation therefore gave room for a high fall. Moreover, the country we were in appeared to be an elevated plateau, to which we had ascended abruptly at Mount Horsefall, and whioh would probably come to an abrupt termination. Wo accordingly started down stream, cross ing a conslderablo tributary on tho right bank just below our oamp, Tho rivor ran through a booch forest, and as nothing will grow under the beech trees, its banks were without that fringo of peculiar vegetation which is usually such a marked feature in an Australian river or creek. After a little we went over to the left bank, and crossed a small creek whioh joined the river on that bank, we then came upon a series of small hills, perhaps altogether fifty or sixty, There was, however, a good indi- cation of something better. We could see a light through the trees ahead as from a largo clear ing. This appearance oould only bo occasioned by the edge of an abrupt decllvity. We pushed on and soon began to get glimpses of a valley a long way below us, and to hear tho roar of a great fall. The beech forest ceased with the edgo of tha declivity, and the slopes below, when not too steep and bare for anything either to grow or stand on, were covered with undergrowth, mostly ti-tree. To see the fall wo must got below it. We accordingly descended as rapidly as a regard for our necks would permit several hundred feot, and made our way on to a Iedge down to the water. From this point we oould see the water fa!ling above and below us over a faoe of dark rocks in a series of steps. The fall was shaded by ti-tree, with occasional tree ferns on the ledges. The spray fell like rain. We were too close to the face of the fall, and tho ledge we were on would not permit us getting further out. We were not the first persons who had viewed the Yarra falls from this spot, for we saw a tree wilh a blaze on it, on whioh was a name, partly overgrown with bark, whioh wo mado out to bo A. Burns. We then crossed over, scrambled along the face of the cliff and made our way down an other hundred feet or two, and got another vlew of tho falls, with, however, the dis- advantage that we were too close to see far up or down. This point was by the barometer 550 feet below the top of tho fall. We could see the fall for about 50 feet bolow it. It was a continuous fall all the way, interrupted only by small ledges. There is, however, no reason to suppose that the lowest point to which we oould see was anywhere near the bottom of the fall. Judging from the appearance of the valley it was far from being so. The total height of the fall therefore, can scarcely be less than 700 feet or 900 feet; it fs probably 1000 feet. We had not seen by any means as much of the falls as wo should have liked, but we were compelled to return. It was Tuesday, and R. had to be In a distant part of Victoria by the following Monday morning for this purpose It was necessary that, he should be in Melbourne by Saturday. Wo could scarcely do this unless we moved on that day. Moreover, our oats were running out, and there was not a scrap of feed at our present camp, while our tracing showed that on the Thompson, 4 miles on, there was grass. We accordingly turned back towards our camp. In returning we got a vlew of a great cascade, forming the top- most rip on the fall, which we had not seen going down. By half-past one we had regained our camp. We then bathed in the Yarra, had lunch, struck our camp, and started for the Thompson, where we hoped to camp that night. It was shown by our tracing to be 4 miles distant. The track in the first instance followed the ridge of the very low spur between the main arm of the Yarra and tho tributary that joined it just below our camp. After a little the track forked; we took, the left fork, which took us down to the tribu- tary at a point where two creeks united to form it; beyond this the track was not apparent. After a little we found a place where a tent bad been pitched, with a rude platform of round tim- ber to raise it off the ground. We had evldently come upon an old surveyor's camp. That explained how it was that the track ran out. We accordingly returned and took tho right hand fork of the track. After we had gone about three quarters of a mile the track turned down to and crossed the oreek on our left, and shortly afterwards began to ascend a ridge on a sideling. The top of this ridge was not. more than 100 feet or so above our camp. On it we found white gum timber. The rldge was narrow, and the track imme- diately descended on a sideling on the other side, about 300 feet Into a narrow valley con- taining a fine stream of water. The sides of the valley were lined with beech trees, with a few tree ferns. This creek must form the right fork of the Yarra as laid down on the maps; and as its level appeared lower than the top of the falls, must join, the left fork below them. Crossing the creek we ascended on a steep sideling on the other side to a height somewhat greater than that from whioh we had descended, and found ourselves in a forest of white gums mixed with beech trees, with a good deal of undergrowth. The creek, however, continued tolerably clear. We were now upon the crest of the dividing range, between the waters of the Yarra and the Thompson, marked on the maps as Wright's range. A little before seven o'clock the track began to descend gently, and we reached a fine stream of water crossing the track from north to south, spanned by a good log bridge. This stream, which was much larger than either fork of the Yarra, or, I should say, than both of them to- gether, we made out to be the Thompson. Here we determined to camp. A little way up from the river, to the right of the track we had come by we found an open glade carpeted with good grass. On this were the remains of an old survey camp, consisting of log plat- forms, similar to that we had noticed on the Yarra. There appeared to be a succession of rich glades along the river, divided only by low scrub, tall timber not being found till some little way up the slopes on either side. There was, therefore, a ciear view up and down tho river for some way over the top of the scrub. We could see the sky, too, over- head and in front of us. All this was a change after the dense grass through whioh we had been travelling for the last four days, The edge of the other valley was lined with large white gums, say 100 foot high, with straight, thick limbs tapering to the top, and wide spreading arms a little more than half way up. The slopes behind were covered with a mass of plants of different kinds. Every here and there above this rose to a great height huge logs, white with age and black with flre, without limbs, broken at the top. Though generally impressed by the view, there was a feeling of solitude connected with this camp not ex- perienced elsewhere in the course of this trip. The height of this camp was 2300 feet above M'Mahon's, or only 100 feet lower than our camp on the Yarra. We were still, however, above a high plateau, as high or higher than the top of Mount Macedon. We were now about 23 miles from Reefton, and about from Mount Lookout. Leader (Melbourne, Vic. : 1862 - 1918), Saturday 17 July 1886, page 16

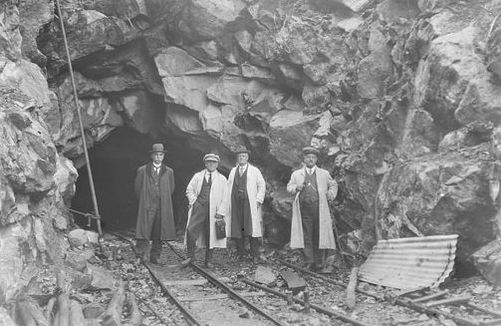

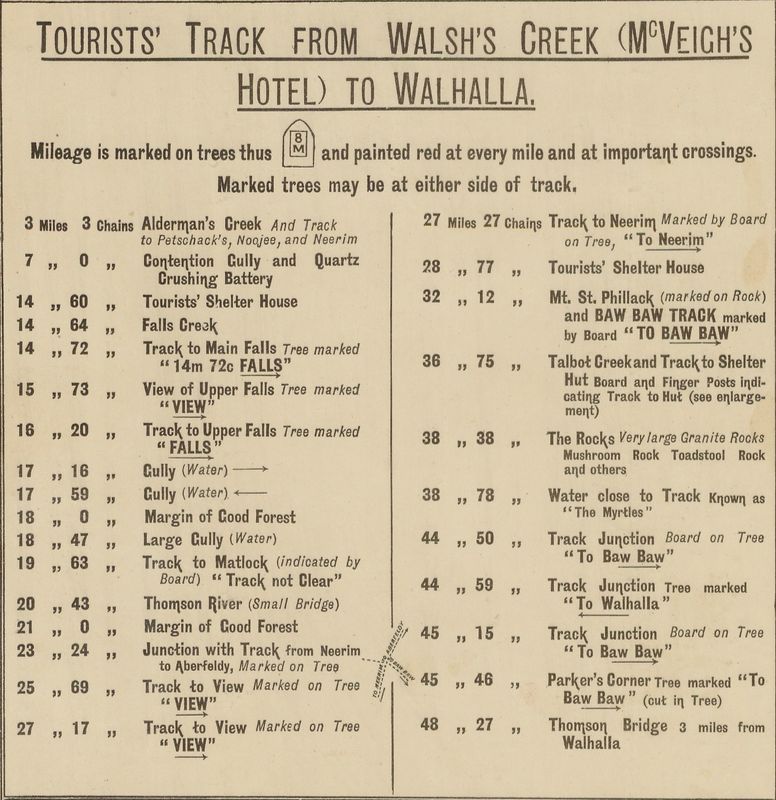

THE TRAVELLER. RAMBLE AMONG THE NORTH GIPPS-LAND HILLS By AN OXFORD GRADUATE . II. A good Government road, though somewhat old, leads up to the township on Mount Lookout. These roads, splendidly constructed, will be of use in opening up the country, which must be important agriculturally in the future, when the mining may have fallen off. Much beef might be grown on these ranges. The glory of Mount Lookout has, however for the present departed. It is melancholy to see the empty and decayed former tenements of man and beast, especially if half obscured by a mantling mist. In the warm sunshine the golden clover paddocks and peaceful cattle must form a more cheerful pic-ture. Truly, agriculture makes a country more lovable than mining, as we found in our next camp on the mud perturbed and reddened stream of the Jordan at Violet Town. At Violet Town not much is doing. There is a little more life at the Red Jacket higher up the stream. Blue Jacket and Jericho are other centres on the Jordan. Here Chinamen abound, working over the alluvial for the third time. From the Jordan valley you climb to Matlock by a steep track still used by drays. Matlock is situated — or was till the greater part was burnt down in a great fire — on the very top of a hill nearly as high as Mount Useful. It served as a store and supply centre for the miners in the good old times, as it lies about four miles from Woods Point, and at about the same distance from Jericho. The whole of the timber has been cleared for a radius of several hundred yards from the summit, which is thus terribly exposed. It had been raining pretty steadily all the night before and during our march from Violet Town ; but just as we entered upon the clearing the tempest burst upon us, bitterly cold wind and rain. Drenched to the skin, and almost driven from the track, we were glad to find that a hotel still exists at the very top of the hill. This is the only house that escaped the great fire in which Matlock was consumed. Our host had stories of the mining days; when Matlock boasted its thirty dancing girls, and when miners drunk nothing cheaper than champagne. He showed us nuggets, too, and gold in the rock, and does not think that "the creeks" are exhausted yet. However that may be, there is plenty of good land up among the hills. Almost any sort of temperate fruits and vegetables can be grown there. The drawback is the cold which is telling in the summer at times, and in the winter must be terrible. For charming views, much resembling those of the famous Huon-road in South Tasmania, commend me to the high track between Matlock and "the Springs" of the Wood's Point-road. Now, we are on a ridge track, and our admiration is divided between the distant peaks to the north and east, with their varied outlines, and the giant many-branched valleys stretching to the S. and W. Now we move along a sidling, and cross fern gullies and mountain streams ; on the upper side of the road waterfalls or mossy bank, on the lower, the widening zone of fern gradually lost in the forest growth below. The air is keen and crisp, and the smart walk communicates a pleasant glow not at all like the sweltering heat of the unsheltered low lands. Near Sinclair, or "the Springs," Mr Coombes, of Melbourne, has a cattle station, and the cattle seem to do well in these cool uplands, which, when the timber is cleared, become perennially green with grass. Leaving the Wood's Point-road, about a mile from the station, we turned south to attempt to make our way through by a new survey track, cut about seven months before by Whitelaw. We had heard of this route at Tanjil, and again at Matlock, but had not obtained correct information as to where it ended, or rather where it began, on the south side. It was 40 miles long, as indicated by the figures cut roughly on the mile trunks, but we remained in the dark as to our exact terminus until we reached it. We soon found that it could not be Moe, and Tangil presently dis-agreed with the bearings and distance as shown by chart and compass. But we were com-mitted to see it through and went forward ac-cordingly. At the end of the first day's march we came into another track, cut previously by Whitelaw, from Reefton to Aberfeldy. Some of our party had been on this two years before, and from them we learnt that the Yarra Falls were accessible. We camped then a day at the junction, in order to visit the falls. Following the old track toward Reefton, with difficulty making out and renewing the blazes, we crossed three small feeders of the Yarra in about three miles. At the last of these, which most de-serves to be considered the main stream, we left the track and made our way some half mile down to the head of the falls. From this point we commanded a grand survey of a wide range of country, all the wide valley of Yarra with its mountain boundaries. By scrambling down over fallen logs, rocks and stumps, through a tangle of vegetation, we can here and there stand at the side of the rushing waters, or at the foot of a fall. Now the waters sweep 20, 40 or 60 feet at one bound ; now they break into a hundred tumultous cascades ; and now roll over mossy rock slopes into fern-fringed pools. Our way back was plain enough from our morning's blaz-ing. The original forest of monster gums was fast dying out. A few enormous old trees towered overhead still. But most were laid low, and no saplings were springing up, but instead, most refreshing to the eye tired of the sombre eucalypts, groves of golden wattle, of beech and of sassafras. From the junction we found, after wasting half a day in the process, that Whitelaw had made use of about three miles of his old track in cutting this second way through the forest. We presently crossed the Thomson, flowing swiftly over sparkling mica sands, and entered a granite country very ugly for travellers. Not merely because of the strewn boulders, but also and chiefly because a forest of dead trees still standing exist alongside of the living timber. The trees cleared from the track are laid along its sides. Trees then falling near the track are liable to fall across it. resting on those felled by tbe axe, just too low for the horse to go under ; just too high for him to clear. Each fallen tree cost us a delay of half an hour, on the average, we computed, owing to the unloading, the de-tour and the re-loading. As tree after tree barred our path we began to wonder whether we should be able to get through, although the track had only been cut so short a time. How ever, after making bat five miles that day we came out from the dead sticks, and progress was then comparatively easy. The course still included heart-rending ups and downs, but water at least was abundant. Two scenes in that virgin forest will never be forgotten by us from their loveliness. One was a nature cleared happy valley embosomed in the hills, bordered in a waving line by the dark woods. Green grass carpeted the whole, save where it was gay with brilliant everlastings and craspedias. A branch of the Thomson meandered through the glade. It seemed, remembering the situation, the beau ideal of a retreat for a brigand, itself the pic-ture of peace. Fain, too, were we to linger on the Tangil as we again came to it on our home ward march. It flows through a gully of huge dimensions. The stately columns of the tree ferns were wreathed with creepers, and hung with festoons of more delicate species. Bright and dark ferns clothed the gully to the water's edge. The mountain shrubs shone in a more luxuriant foliage. Woody climbers stretched from tree to tree across the river, or upwards from branch to branch. Below the water was flowing dark, clear, cold, steady, swift. After leaving the Tangil, and accomplishing a last climb of 700 feet, we gradually sank again, and camped by the Jay Creek. We now began to make out our bearings, and the next day came to the end of the mysterious track of Russell's Creek. Thence a day's march brought us to Moe. This new track of Whitelaw's thus afforded us a rare chance of seeing this entirely new forest country. It will probably share the fate of the Reefton track, and in a few years be obscured by the scrub and blocked by the fallen timber. The country undoubtedly is rough, but there is an ultimate future for it. There is much rich land hidden away in those fastnesses of nature — land of mush and hazel and of blanket tree, as well as of beech and of sassafras. Most likely gold will be found in the Silurian strata; possibly tin in the granite ridges. But this can hardly be yet. The views are wildly grand, and we esteemed ourselves happy in being amongst the first to penetrate this Victorian Highland forest, as yet unspoiled by the ravages of axe and of fire. it. Over the Baw Baws To the Editor of the Argus Sir, - May I direct the attention of tourists generally to the state of things prevailing on the track from Warburton to Walhalla over the Baw Baw Mountains? It is time that an accurate account of the journey was published to prevent tourists from entering on a arduous and disappointing trip. The chief incentive for making the journey are a handbook issued by the Victorian Railways and the map printed by the Department of Lands and Survey, both misleading. First of all, in regard to the actual track, the railway book says :- "The Lands and Public works department have cut a track, well defined and easily followed, and have erected three shelter sheds en route at convenient distances apart." The first part of this statement probably has some truth in it at first, but now conveys an utterly erroneous impression. At the head of the map we are told " Mileage is marked on trees and painted red at every mile, and at important crossings. Marked trees may be either side of the track. " Yes they maybe, but as a matter of fact, they are not. There are not more than six of the 50 odd miles of the journey marked off - the track, once made, having been neglected ever since, with the result that, owing to the fires which constantly ravage the country, one has frequently to climb over or go around dozens of large fallen tree-trunks to the mile - a tiresome operation with four days' provisions and bedding carried on the back. A certain 200 yards between Falls creek and the River Thompson takes nearly a quarter of an hour to negotiate for this reason. As a whole, the track is either obliterated by trees or is over rough, loose stones, which cut boots to pieces, or leads through stretches of morass, in which the hoofs of struggling pack horses have cut deep hole, and ruts, making walking extremely unpleasant, often involving long deviations. To the "townie" the difficulty of following the track must be great. In some places on the Plateau there are no blazes to be seen on the trees for miles, while one- continually comes across diverging tracks and dreads to take the wrong one. At a certain spot; 19 odd miles from McVeigh's, the track splits into two and there is absolutely nothing to prevent the unwary from taking the left hand to Matlock, he perhaps going 10 miles,before the mistake is found out. But the greatest objection of all is the real length of the journey. On this point even the two Government publications differ. The tourist should be informed that the distances on the map are as the crow flies from peak to peak, and are not the actual distances passed over by the traveller, who invariably has to descend into steep valleys. and toil up opposite slopes by circuitous deviations. The huts themselves are of a most elementary type, the middle having mother earth for a floor. It and the Talbot creek shelter shed are on par for filthiness, particularly the latter. Hundreds of tins that once contained provisions are littered around the doors, forming ideal breeding grounds for blow flies and vermin, swarms of the former making a meal a most disgusting process, since they settle in droves on any food that is opened. A ganger should be sent through the track once or twice a season to clear the way, and clean up the immediate vicinity of the shelter sheds. yours, L. Tree blaze at the 16 mile 20 chains point

Over the Baw Baws

To the Editor of the Argus Sir,- Having myself taken the trip from Warburton to Walhalla across the Baw Baws, I read " L's "letter with much interest, which was not unmixed with surprise. My companion and I commenced the trip on January 10, thus crossing the track subsequently to the great bulk of Christmas and New Year trippers. If anyone had left the track in disorder it would most certainly be these, yet not at any point did we find the offensive condition of things to prevail as described by " L ". Those unwritten laws which bind the fraternity of the track had been observed to perfection, and the cleanliness and considerateness of previous tenants of the shelter huts left nothing to be desired. The track, as stated in the booklet issued by the Lands and Survey department is well defined, and easy followed. At no point could the veriest "townie" if he had his wits about him, lose his way. The blazes on the trees are large and of a highly distinctive shape, except on top of the plateau where for about 14 miles the timber is small and dead. Even here scrutiny will always reveal them to the anxious tourist. With regard to wondering off on a side track, such a prospect would only appeal to one with no eyes for the direction he was pursuing. The absence of blazes of the distinctive shape above mentioned would immediately commend itself to the ordinary observant if he were on the wrong track. The statement that no more than six mile-posts are marked is totally unfounded. For the first 23 and the last 14 miles - the exception being the stretch at the top of the plateau - the markings of the mileage is so plain and masterly as to be an object of comment among certain persons who have done the trip. With regard to the difficulty of negotiating the stretch between the Falls and the Thomson river, I recollect nothing. This part of the journey lives in my memory on account of the extreme beauty and magnificence of its timber. The shelter-houses are indeed primitive, but offer a haven of refuge to the weary and possibly half-frozen travellers. The liberal supply of stretchers and cooking utensils adds to their already substantial supply of comfort. yours Defender.

Visit to the forgotten waterfalls of Deep Creek a tributary of the O'Shannassy River Scaling East Wall of Acheron Valley What Walkers Found ( By a Special Correspondent ) Tourists who have driven through the Acheron Valley, from Narbethong to Warburton, or have walked along the old pack track that rambled along, crossing tributary after tributary of the Acheron River, might have wondered what the valley was like off the beaten track, and what a closer view would reveal of the walls which the Great Dividing Range hems the valley. My curiosity got the better of me and I found a curious formation, the Dividing Range, after reaching Mount Strickland, takes a sudden dip to the southward to within a few miles of Warburton and Mount Donna Buang then suddenly it turns to the north and passing over Mount Vinegar, crosses the Blacks Spur and resumes its normal east-west course over Mount Monda and St Leonard. Such a vicious bite southward of a northward flowing river provides something unusual for the tourist. The little track that wound southward from Narbethong in 1923 has been surplanted by the Acheron Way and something of the awe-inspiring nature of the trip through the valley has been lost. Still the valley provides new material for many holidays. Track marked "indistinct" In Easter 1929 we chose the East Wall. Those who know the tourist map of the district will recall a track marked on the map that starts from the Splitter's Camp near the extreme south of the valley and winds northward over the Divide to the summit of Mount Strickland. This track has tantalisingly been marked " Track indistinct " by the tourist authorities and they warn that the track is overgrown and that they cannot advise you to attempt to follow it. The beginning of this track is a few yards due east of the hut at Slitters Camp. After following it straight up the spur for about a mile, it lost itself completely in the undergrowth. The way was straight up the spur and we went on. After scrambling and pushing we reached the brow of the spur. The undergrowth suddenly petered out and gave way to snow grass and box, which formed a park like plateau land. There were several miles of this park-like land along this part of the Divide, and this stage of the journey is comparatively easy. 4250 feet up Following the spur in a nor'-nor' easterly direction for about four miles brought us to the summit marked on the tourist map "4250" - the highest point in the district. Once the spur from Splitters Camp is climbed the rise is gradual all the way to this summit. A car could negotiate with ease. Halfway from the Splitters Camp Spur to the "4250" point a true plateau formally occurs where it seems that this spur makes a junction with the Dividing Range proper. An area a mile square seems to sweep gradually upward and concentrate on a certain point crowned with a cap of snow gums. The area is covered with fallen timber, and the standing trunks of dead stunted gums like the dried skeletons of some arboreal shambles. The only living thing is the snow grass. Standing on the southern rim of this plateau one gets the impression that the whole earth is sweeping majestically upward to one central point. After crossing this plateau, the top of the Divide, although still wide, is more normal in size. Although freely dotted with clumps of snow gums, the park like nature of the country continues until on the verge of a rapid descent northward, it culminated in the "4250" point. Fine view through gums Snow gums at present mar what would undoubtedly be the finest view point in the district. It is necessary to move from point to point to obtain views in different directions. To the northward are the closely wooded top of Mount Strickland, on the left, the beginning of the Poley Ranges on the right, and between them the westerly portion of the O'Shannassy watershed. Directly to the north over the Paradise Plains can be seen Mount Kitchener, beyond which lies Marysville and still further away Cathedral Mountain and the plains around Buxton. To the right of Mount Kitchener is mount Grant and Mount Arnold. Snowy Hill and Lake Mountain ridge stretching away to the north. On the west of the "4250" point the immediate foreground is the steep valley of the Acheron looking more precipitous than ever from the perch on the eastern rim. Mount Vinegar rises directly opposite. Beyond Mount Vinegar lie Mounts Monda and St Leonard an Mount Macedon. South of these are the plains of Melbourne, Port Phillip Bay with the You Yangs in the distance. Southward are the Acheron Gap through which we had come from Warburton and Mount Donna Buang with the lookout tower clear against the skyline. Sudden dip Continuing northward, the ridge of the Divide dips steeply. The dip ceases abruptly, after a mile, in an unbroken rise to Mount Strickland four or five miles further north. Our descent was hampered by fallen timber and dense clumps of snow gums. The gap, at the foot of this descent, is a pleasant surprise. Tall trees with a carpet of snow grass, and walled on the north by a grove of beech trees, made a pleasing picture. This beech grove is on a spring which forms the headwaters of one of the many westward flowing tributaries of the Acheron river. Our next objective was the falls on the headwaters of the southern most tributary of Deep creek in the O'Shannassy watershed. It is only a mile from the Gap but the country is tricky. Use of the compass and some head work got us there without much trouble. The first part of this stage of the journey is through a desolate piece of fire swept country, thickly covered in fallen timber and dead gum saplings. The last stage is along a creek lined with beech trees until within 200 or 300 yards of the falls the creek joins the main stream. Falls drop 200 feet The falls have a total drop of more than 200 feet. Unlike Steavenson's falls Marysville, they lack the majesty of a single long fall, but leap from ledge to ledge in drops from four to twenty feet. We climbed down the falls and up again. It is an exhilarating scramble and does not present any uncomfortable situations.

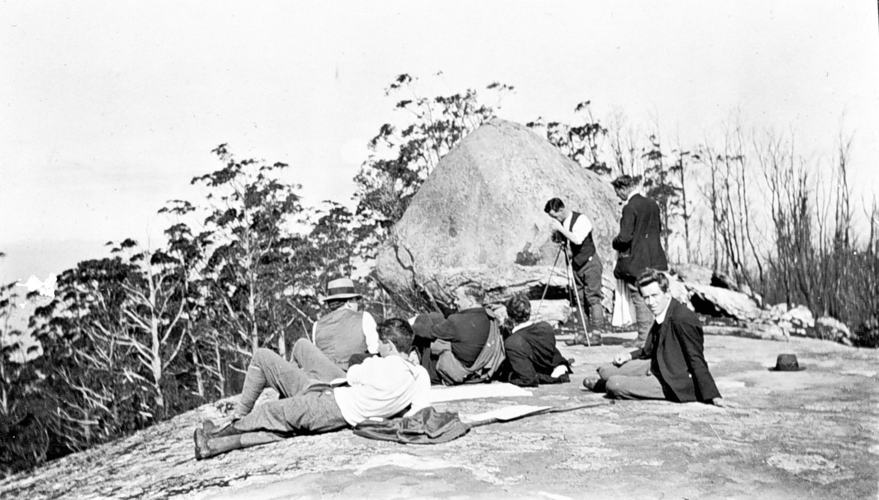

Photos above are near the 4250 feet point which is known as Mount Ritchie.

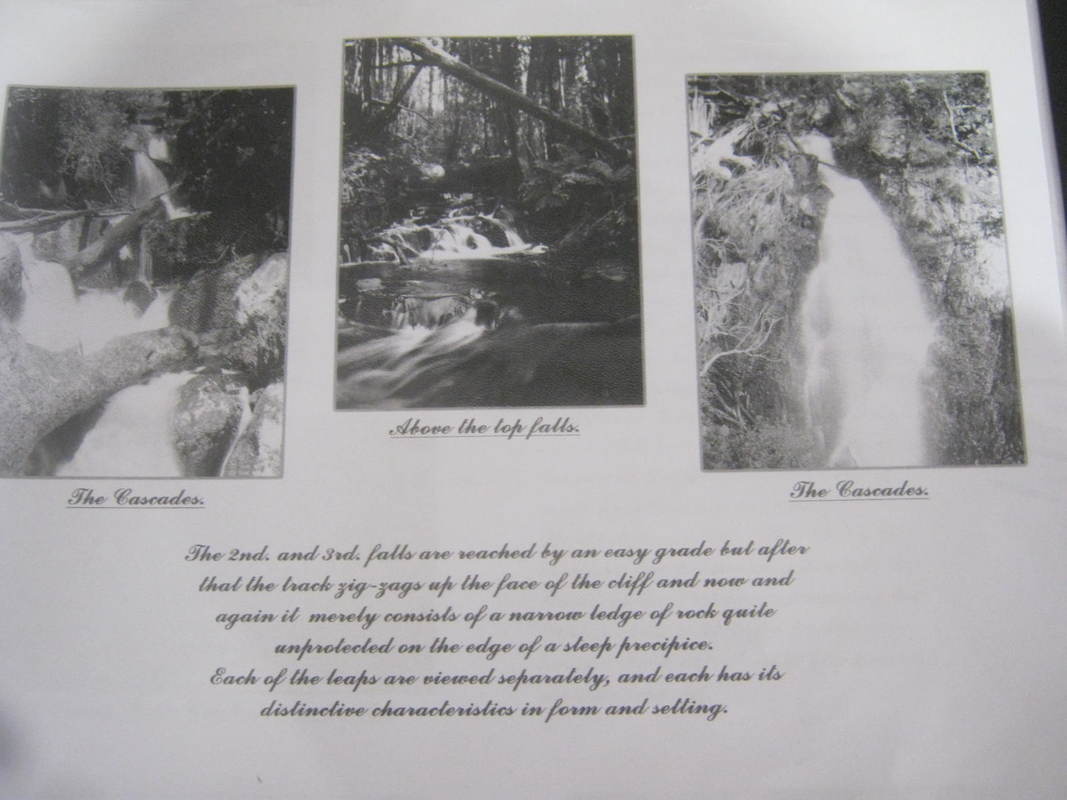

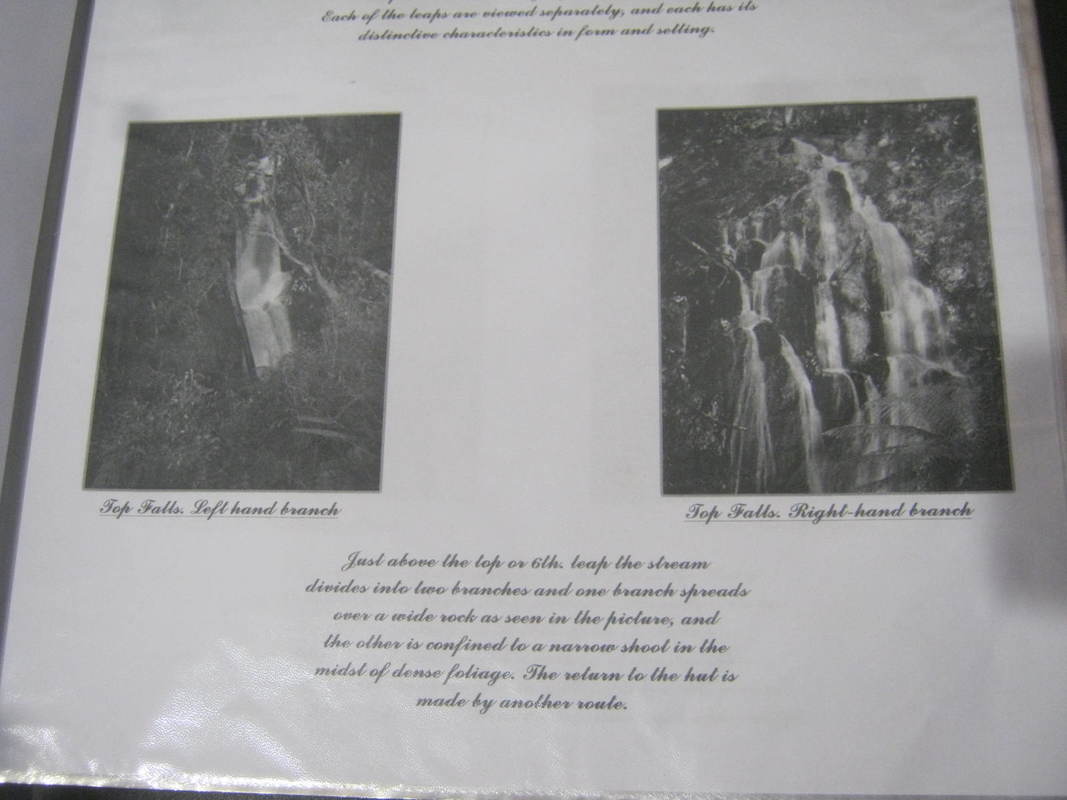

Easter Walking Over the Baw Baws By R. J. OKeefe The route from Warburton to Walhalla (" over the Baw Baws" ) seems to have been designed specially for an Easter walking tour. Actually the track starts from McVeigh, 22 miles from Warburton, and picks up the little mining town of Walhalla after traversing just 50 miles of beautiful and interesting scenery. The triper may take as long as he likes on the track, but he cannot enjoy it in less than four days. It will be as well to have arranged beforehand a car to meet the train for the 22 mile run to McVeigh's. Cars will do the trip for 50/ costing very little more than the coach. McVeigh's will be reached at about 10 p.m. if the afternoon train is taken from Melbourne. Here the track leaves the Woods' Point road. There is no difficulty in finding it, but, anyhow, the people at the hotel will direct tourists. As the moon is full at Easter, it would do no harm to go out about three miles, to where the track crosses the Alderman's creek. The reason for going to Alderman's is that the first section of the track ( to the Yarra Falls Hut ) is so beautiful that the walk ( 14 3/4 miles ) would take more than a whole day. It is always desirable to lunch by a creek, and for this purpose there are small creeks at every few miles along this section. The second night will find the party at Yarra Falls Shelter Hut. These huts are always crowded at Easter, and I prefer to sleep under the stars. At about 200 yards beyond the Yarra seems to be a favourite spot for campfires. The hard ground can be softened with bracken. The next day's trip will be the most strenuous. For the first two miles from the hut it is hard going, the first half-mile very much so. There is only one thing to do - plug along with frequent rests. But after the first two miles ( to which one and a half hours should be allotted ), the gradient is a very pleasant one. The headwaters of the Yarra will be crossed at 18 1/2 miles, and here is a good stopping place for lunch. Or lunch may be taken at the bridge over the Thomson at 20 1/2 miles. The afternoon stage of the walk is also uphill, but not steep, but too much time ought not to be spent on dinner. Mount Whitelaw hut is a bit off the main track, and will not be seen until the bye-track |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Categories |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- HOME

- About

- Contact

- Bush Camp News

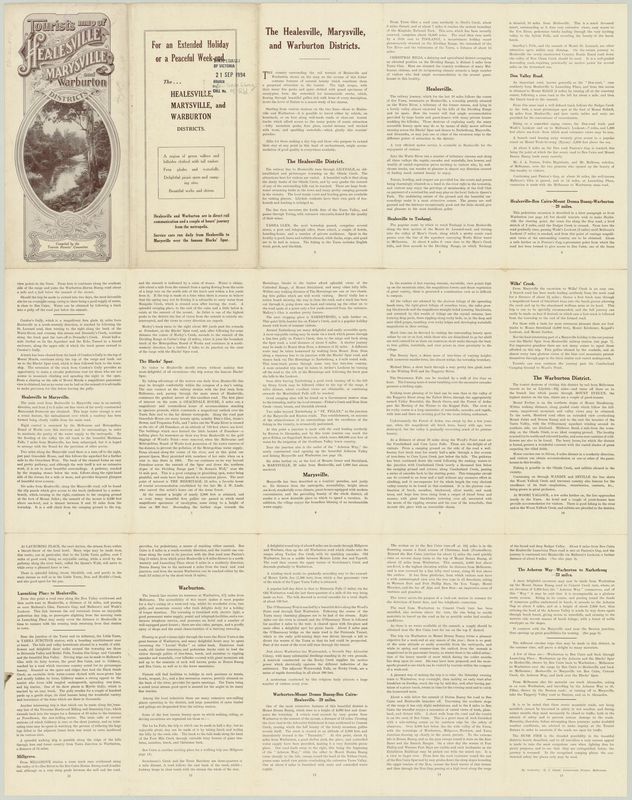

- Companion Guide to Healesville

- YARRA RANGES NATIONAL PARK

- Historic Photographs Yarra Ranges National Park

- Dr Annie Yoffa's 1928 Walk from Warburton to Walhalla

- Black Spur

- O'Shannassy Aqueduct

- Graceburn Weir

- Badger Weir

- Donnelly's Weir

- Maroondah Dam

- Mt. Donna Buang

- Cement Creek

- Upper Yarra Dam

- Fernshaw

- Cambarville

- Mt St Leonard

- Yarra Track 1895

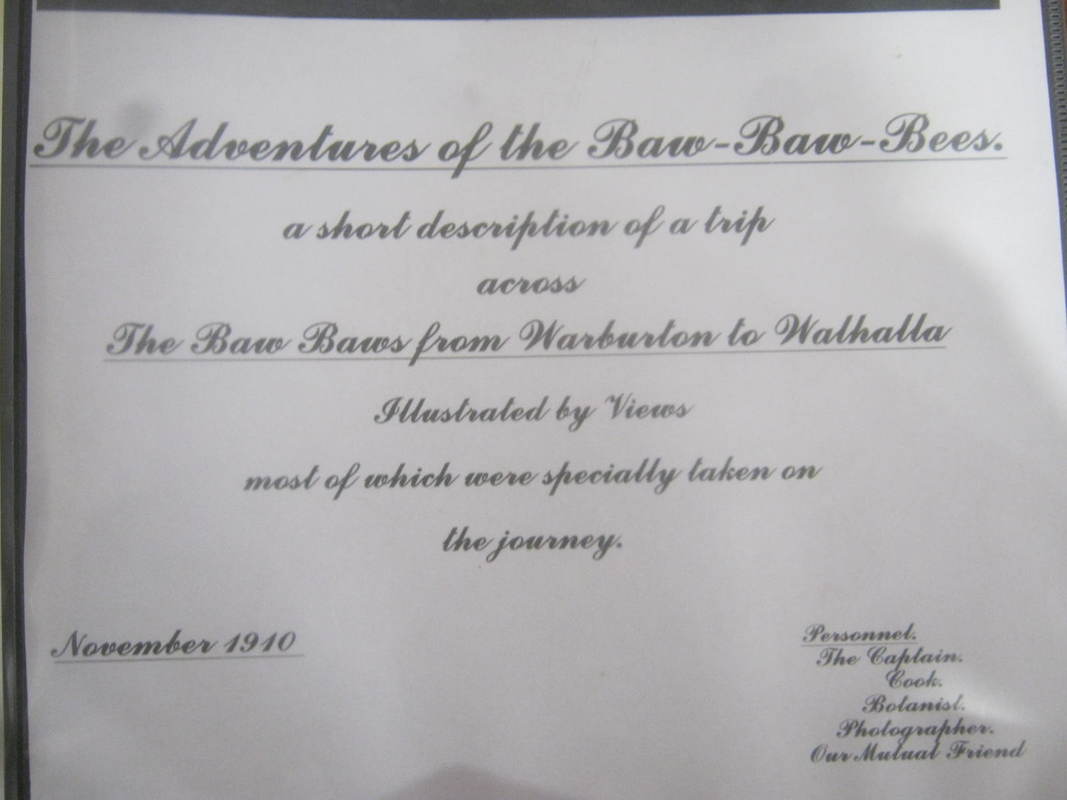

- Warburton to Walhalla 1928 Easter Expedition

- Donnelly's Weir

- Dr Annie Yoffa's 1928 Walk from Warburton to Walhalla via Yarra Falls

- Baw Baw track

- WarburtonVerticalK

- Blog

RSS Feed

RSS Feed